The newly opened education centre, Kunskapshuset, in Gällivare is certainly eye-catching. The asymmetric, bright red façade over six floors is lined with a combination of glass and externally affixed glulam columns arranged in pairs. The external columns provide both decoration and sun screening, and are connected to load-bearing posts in the same position on the inside. Standing directly in front of the façade, it initially looks completely glazed. But as soon as you see it from the side, it immediately becomes a billowing wave of red wood. The roof slopes in different directions, the façade shoots out in unexpected ways and the interval between the paired columns varies.

Initially, Lars Olausson and Jonas Hermansson had the idea of making the entire building in wood, but this proved far too complicated.

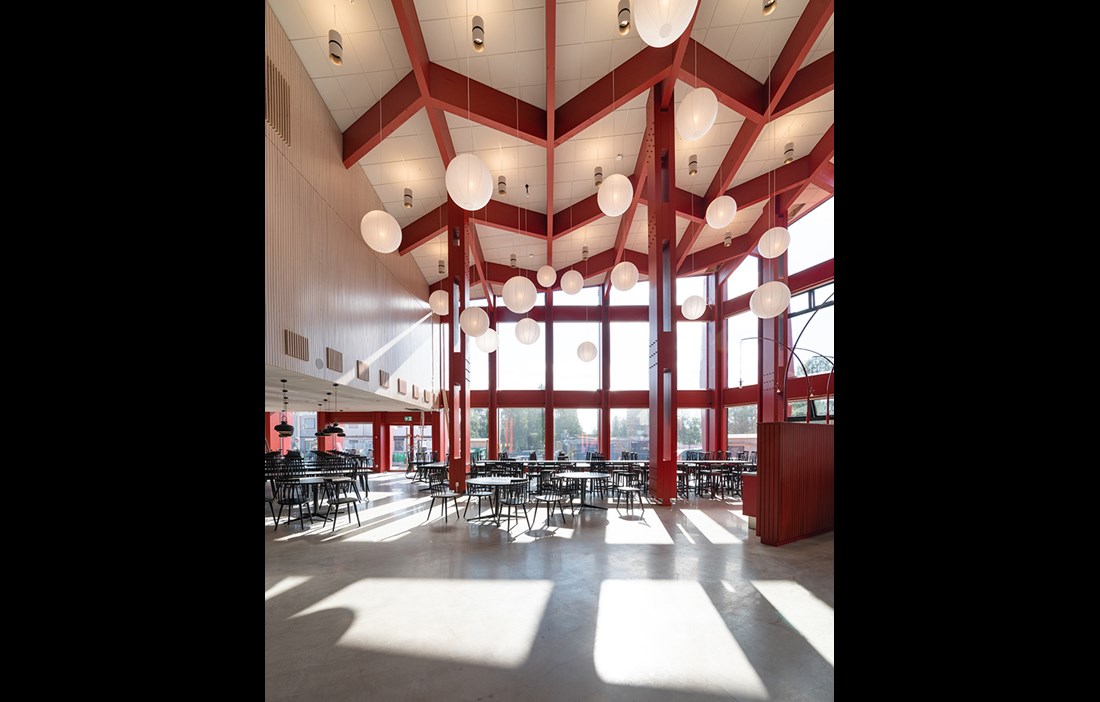

“The local council thought it would be too much of an unknown quantity as the building is so complex, so we chose a combination of wood, steel and concrete for the load-bearing structure. To retain the feel of wood, we have elected to keep it exposed, particularly in the communal areas such as the canteen and the entrance, where it is also the structural frame,” explains Lars Olausson, lead architect at Liljewall, who designed the building together with his colleague, interior architect Jonas Hermansson.

Kunskapshuset is part of the urban transformation that Gällivare is currently experiencing. In a relatively short time, what remains of the neighbouring town of Malmberget is set to be demolished or moved and the community incorporated into Gällivare to make way for the continued expansion of the mine.

“Many of the local authority’s public buildings were in Malmberget. When we realised that we would have to move the whole community, we drew up a vision to build a world-class Arctic town. One of the strategies was to create movement and activity in the centre by placing some of the larger public buildings there. The new Kunskapshuset, with its upper secondary school and adult education centre, is a key element of this. And it has really become a striking landmark,” comments Lennart Johansson who, as head of the Department of Community Planning at Gällivare Municipality, has had overall responsibility for the process.

Building the new Kunskapshuset threw up many challenges. First there was the fact that a total of 24,000 square metres, including parking, had to be squeezed into an extremely limited space. The various façades would also face four very different settings – the square, the main shopping street, the church and the town hall. The client wanted a landmark building, but not one that would take over the entire town. And it would have to house just as many students and programmes as before, but with around 6,500 square metres less space.

“To get a feel for the local landscape and a sense of place, Jonas and I travelled up and went hiking in the area. We even spontaneously decided to spend a night in a Sami cabin by Stora Sjöfallet. We then carried the autumnal reds of the marshlands over into the building,” says Lars Olausson.

In addition to taking inspiration from nature, they also wanted the building to reflect Sami culture and the mine that has such a tangible presence in the area, with large open-cast pits and slag heaps. The red wood on the façade continues inside the building via the corresponding red glulam posts on the inside. Another key detail inspired by the landscape of northern Sweden is the modular seating in red painted pine that recurs in several places both inside and outside the building. This was designed by architect Jonas Hermansson at Liljewall and was produced in partnership with Nola specifically for Kunskapshuset. The entrance hall displays its influences in the steel staircase, the concrete floor and the tall fireplace, which is why it is known as the Mine. The external entrance and ventilation hoods on the roof are clad in a brass-like copper alloy from the copper mine in Aitik. Sami heritage is incorporated in various places, not least in an artwork integrated into a 21 metre long part of the façade, created by Sami painter Anders Sunna, glass artist Monica Edmondson and textile artist Britta Marakatt-Labba.

Sami tradition has also become part of the actual architecture and structure. The outer sun-screening columns in the façade are inspired by Sami runes and the load-bearing structure of red painted glulam beams in the canteen ceiling follows an angular Sami pattern.

Wood has ended up being the load-bearing material for three parts of the building: the 23 metre high entrance hall and equally high canteen, the café section and the top level on the seventh floor which houses conference rooms, saunas and a terrace with mountain views of Dundret. The wooden roof structure comprises large, red painted glulam beams in a zigzag pattern, with panels of CLT on top.

“There is no load-bearing metal roofing – panels of wood take up the load in the roof as well,” says Erik Modig, who was chief structural engineer for WSP in the first part of the project.

Each zig-zag wave is then connected to the paired columns in the façade, which are glulam, and in some places also to additional interior glulam supporting posts.

The rest of the structural frame is a combination of steel or glulam posts and a concrete floor.

“Throughout the building, we’ve used concealed screws, hangers and nail plates as fixings. The only things that stick out are the fasteners for the wing-like columns on the exterior. For this the architect specified black painted bolts that form an attractive detail and pattern,” states Peder Eriksson, structural engineer at WSP and wood project planner.

Both the CLT in the roof and the glulam for the façade, roof and internal posts in the canteen and entrance hall are made of spruce. Glulam also features in interior details such as the benches in the canteen, where visitors have their meals. The ribbed spruce cladding that lines various walls in the building is another distinct hit of wood, along with the seating and steps in smoked end-grain oak, with contrasting pine steps at the transitions.

“Steel ties have been used to suspend the staircase from the glulam roof structure, which in turn is tied to the glazed façade. This was one of the biggest technical challenges of the project. But now we have a stable structure with no sway that we are happy is completely secure,” says Erik Modig.

The plan was for the whole building to be completed in May. However, the coronavirus pandemic hit Gällivare hard, which put a spanner in the works, due to delayed deliveries and because many of the contractors involved were subject to travel restrictions. This meant that the building was finished on practically the same day that the new term began.

“Naturally, this caused a great deal of stress at the time, but now it feels fantastic to have been able to open the building. From the feedback we’ve had, everyone who lives here thinks it’s fantastic,” concludes Lennart Johansson.

Text Sara Bergqvist