The dark, robust façade sits discreetly on the rural plot. Here, in the Roslagen archipelago, the chilly winds of the rugged coast meet the island’s warm and sunny glades. The holiday home is located right on the border, with one side facing the sea, and therefore had to be both open and closed to the changing landscape.

“A key element of the home’s architectural concept was that it should be honest and simple, and make use of solid, durable materials,” says architect Gustav Appell.

The house has quickly blended in to become a fixture of the area, largely thanks to its façade, inspired by the Japanese shou sugi ban technique, which involves burning the cladding. The result is a charred surface and a durable material that requires minimal maintenance. The technique remains uncommon in Sweden, and none of the construction team had used this method before, so it was a case of trial and error for everyone, including carpenter Niklas Lundblad. Gustav Appell describes the method as easier than you might think.

“They used a gas torch, the same kind you use to lay roofing felt. Of course, it does take a bit of practice to get the right look.”

They therefore tried burning the first few small areas for different lengths of time and over several rounds, to see which result they wanted to use. Then the cladding was cleaned with a wire brush, installed and finally treated with linseed oil.

“The time it took and the overall cost came in at around the same as it would if we’d painted the house, with the difference that future maintenance will not require nearly as much work. Minimising the need for maintenance was a clear part of the brief from the family. What’s more, the façade has exactly the special look we were after. Rough, but with a soft, tactile surface,” says Gustav.

The combination of the muted façade and the light roof in corrugated zinc creates an exciting picture. There were many reasons for choosing zinc.

“It’s a maintenance-free material, it ages attractively and in its corrugated form it has a clear and distinctive appearance that matches the unusual façade,” Gustav explains.

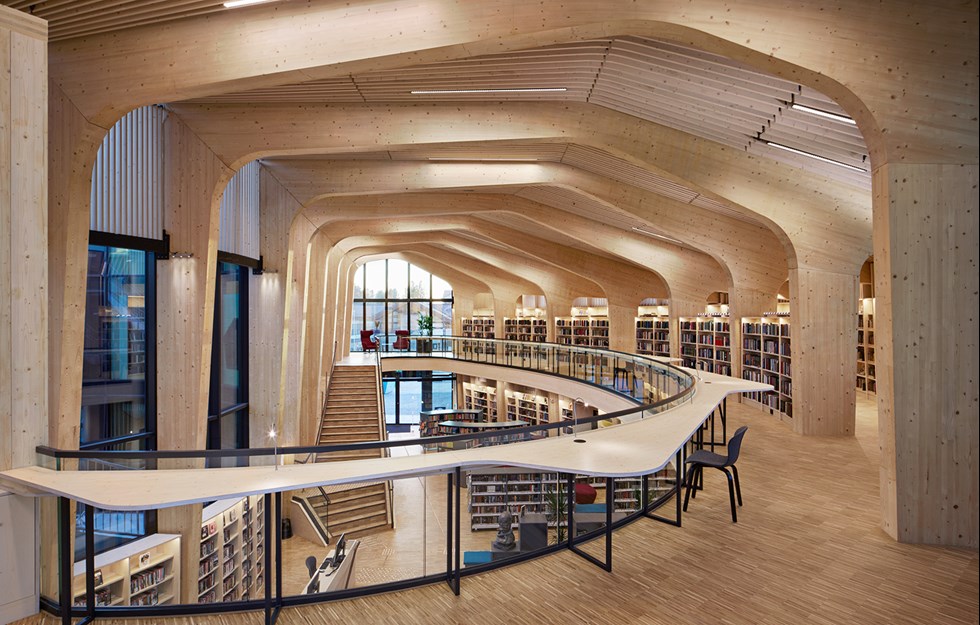

Many of the structural and technical solutions follow traditional building methods, with mineral wool insulation and a concrete floor with inset underfloor heating and a polished, untreated surface. Coupled with generous glazed sections that can be slid all the way to one side during warm days for full contact with the outdoors, the floor offers a distinct contrast with the rest of the interior, which is entirely made of wood, with walls finished in pine plywood and an exposed roof structure, also in pine.

“The relationship between the different materials creates a harmony and makes sure the wood isn’t too dominant. At the same time, it was important for us to reveal the wood internally as well, to emphasise the architectural concept – to show that this is a wooden house. It’s meant to come across as a handcrafted building that is easy to understand.”

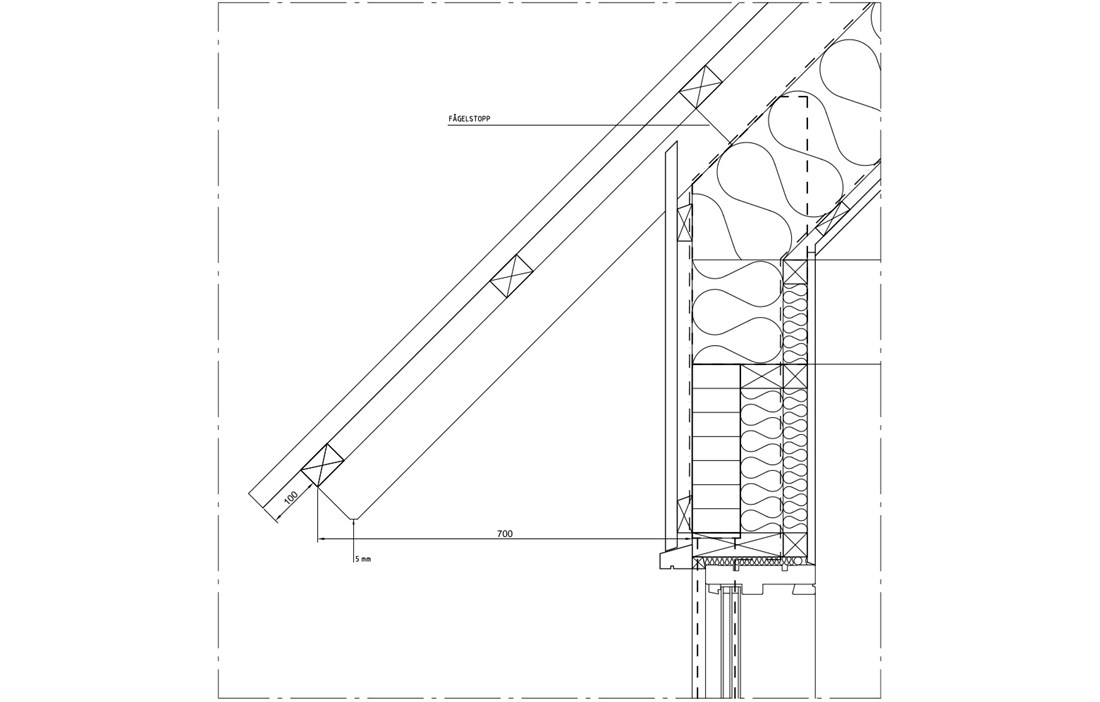

The eye-catching roof is designed to give the long room added character. It had to be possible to build the structure on site, and it had to be attractive enough to be left exposed. The wood used for the exposed roof trusses is premium, knot-free timber, the dimensions of which were chosen partly for aesthetic reasons. The sturdy 45x195 millimetre beams contrast with the slimmer forked uprights, a 22x120 millimetre board on each side of the centrepoint on the beam. The upper frame is connected to the lower one in a simple manner with nailed plywood plates (node reinforcement) hidden inside the wall. However, the uprights are fixed to the beams with a prominent stainless steel bolt, washer and nut.

“The whole house, and everything we do, features a conscious and creative relationship with the structure. It should be allowed to influence the design and the architecture, and the fact that it’s clearly visible only enriches the building,” says Gustav Appell.

Text Johanna Lundeberg