Having views of nature and greenery brings clear benefits for patients, as Professor Roger Ulrichs of Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg told us all back in the 1990s. According to his research, patients who are exposed to plants feel better and return to health more quickly. Since then a number of Swedish and international studies have confirmed similar theories. There are strong indications that just a glimpse of trees and fields can promote health – something of which French architect Marc-Antoine Richard-Kowienski is also keenly aware.

Four years ago, he and his colleagues at the firm Maaj Architectes were commissioned to design a new medical centre in the town of Taverny, outside Paris. The client, Taverny local authority, had two specific requirements: that the centre would gather a range of medical services under one roof and that the building would be a modern and eco-friendly addition to the townscape. The assignment required a great deal of careful thought and deliberation about materials and their properties.

“We wanted to optimise local natural resources, aid the local economy and increase the value of traditional know-how. We also wanted to create a relationship with the wider built environment. We were able to achieve this simply by using a renewable building material – wood,” says Marc-Antoine Richard-Kowienski.

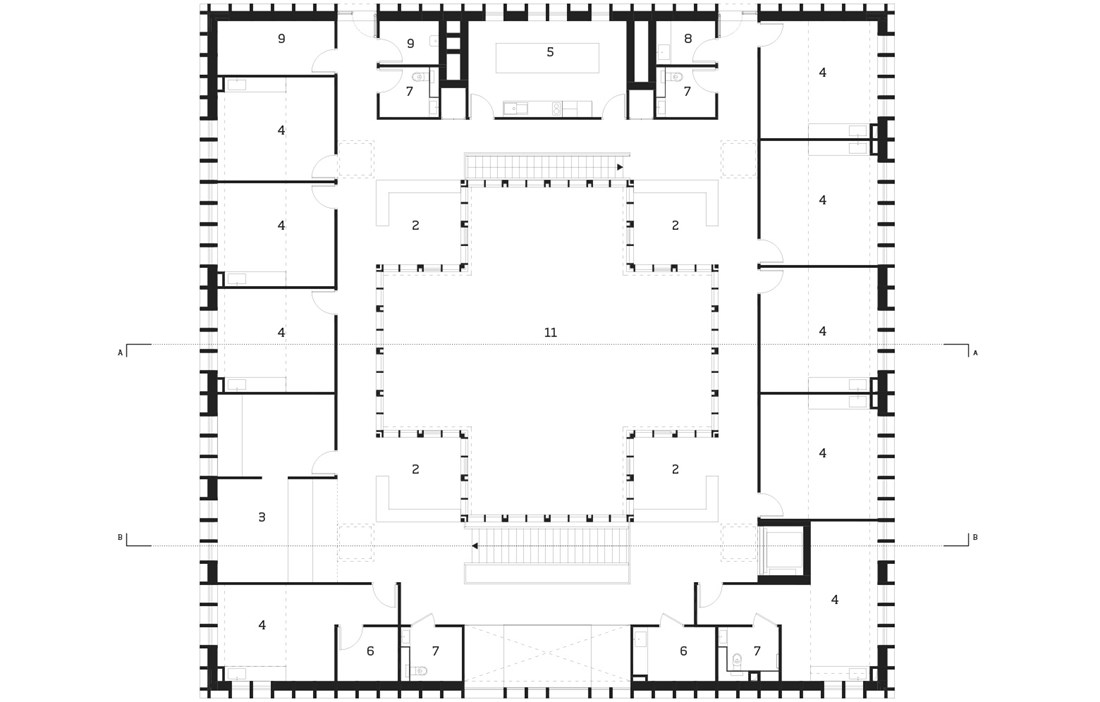

The architects began sketching out a square structure entirely in wood, enclosing an outdoor space at the centre. They took inspiration from ancient monasteries and organised the interior spaces to make the most of this courtyard.

“Because the medical centre is located in a fragmented townscape, alongside a motorway, we wanted to design the building around a central courtyard. This brought several advantages, including natural light for the whole building. The quadratic shape made it possible to organise the departments and consulting rooms in a functional way, around the outdoor space, which makes it an extension of the waiting rooms. It also serves as an intimate sensory place where medicinal plants grow, a reminder of the centre’s health and curative purpose,” explains Marc-Antoine.

The medical centre opened in July 2019, placing a building with two discrete floors and a façade of untreated spruce at the heart of the town. A quartet of four-sided roofs rise up like towers in each corner, giving the square building the feel of a castle or fortress. This impression is accentuated by the dimensions of the façade’s glulam beams and the many narrow window apertures that maximise privacy and shut out noise from the busy crossroads outside. Mass timber has been used for both the façade cladding and structural frame, partly for its strength and capacity to store carbon dioxide, and partly due to wood’s hygroscopic properties, which means its natural capacity to absorb and release moisture, further contributing to the wellness of the patients.

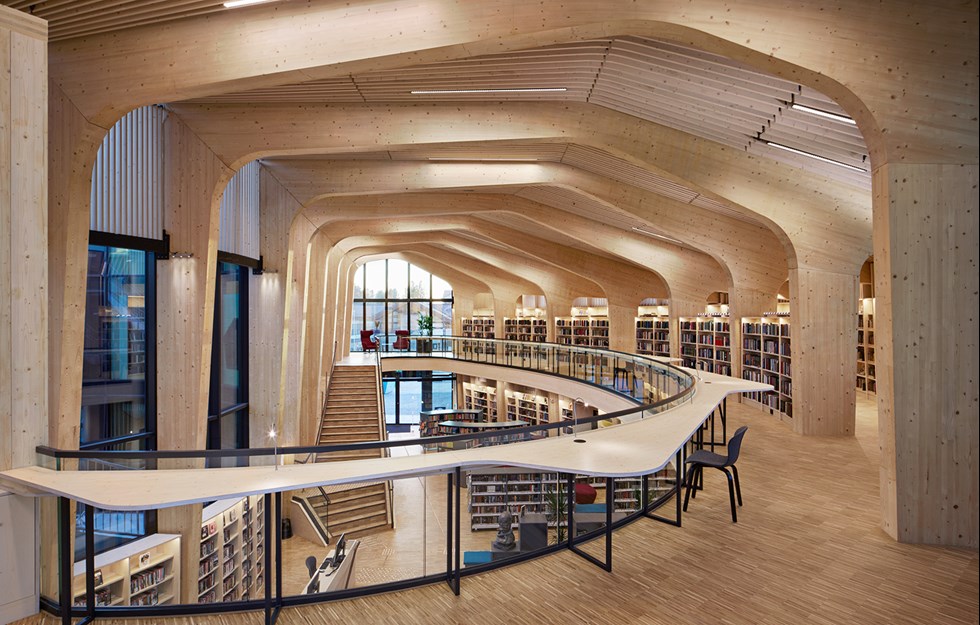

“Wood gives a natural feeling of wellbeing, which is an essential property for a place of health and healing. The material comes across as light and pleasant, delivering the personal atmosphere we wanted,” says Marc-Antoine.

The structural frame is made from glulam beams in Douglas fir, while the floor structure between the two storeys uses CLT. The four-sided roof is constructed from traditional roof trusses, also in the same fir. All the frame and wall elements were prefabricated in a joinery factory in north-east France, less than 200 km from Taverny. The wood comes from French forests in the region of Jura, on the Swiss border, and was sawn at local sawmills.

The wood has a natural resistance to rot, and the façade has been left untreated so that it will silver over time. The overhanging roof structure protects the façade from downpours, while a concrete plinth raises the timber 20 centimetres from the ground. Where the different materials meet, a shadow gap has been used, giving the illusion of the wall hanging in the air, when in fact it is resting on a profile mounted in the concrete plinth. The same principle has also been applied internally between different elements such as posts and windows.

When it comes to fire safety, the architects were forced to go back to the drawing board during the planning phase. This was due to revisions required by the French health and safety authorities, because they felt there was a lack of proper evacuation routes.

“We always try to turn challenges into positives, and this was one of those occasions. The authorities said there had to be a direct link between the roof and the inner courtyard, so we decided to design wooden ladders that were integrated into the look of the outdoor space, as a central and essential component of the architecture,” says Marc-Antoine.

Another result of the official inspections is the wood fibre boards used in the ceilings. They meet the demand for suitable room acoustics by absorbing the reverberation of voices and movements in the rooms.

Exposed wood, not least around the windows, lends a warm feel to the otherwise austere hospital aesthetic. Daylight floods in through the glazing and makes the waiting rooms feel like an extension of the outdoor space, exactly as intended on the drawing board.

“The planting is a reminder of the medical centre’s health-promoting purpose, but it also contributes to natural ventilation of the building. Circulating the air via the surface layer of the ground makes use of the substrate’s natural warmth. This helps to keep the building cool in summer and warm in winter, without mechanical ventilation,” explains Marc-Antoine Richard-Kowienski, who also points out that wood has many benefits, as will no doubt have been seen this past spring, with the restrictions brought by the Covid-19 pandemic:

“We have no up-to-date information about how things have gone at the medical centre during the crisis, but we would guess that the choice of material and the architecture, with well separated departments and few doors, limit the ability of the virus to spread. The effective air circulation also helps.”

Text Annika Munter