All materials must be part of a circular system where the resources are recycled in an efficient way. This is becoming an increasingly common element of sustainable construction, and might, for example, involve reusing existing buildings and adding extensions to meet the demand for new residential and commercial properties. This is a clever way of increasing the density of our cities while also reducing the waste of resources thanks to fewer deliveries and better use of existing infrastructure.

“The biggest driver of wood construction is the issue of climate change, but the megatrend is definitely urbanisation, and that means making our cities bigger and denser in a built environment where people already live and work. In this context the smart choice is to use a circular business model where you give existing buildings a new lease of life with the help of extensions in wood,” says Susanne Rudenstam, head of the Swedish Wood Building Council.

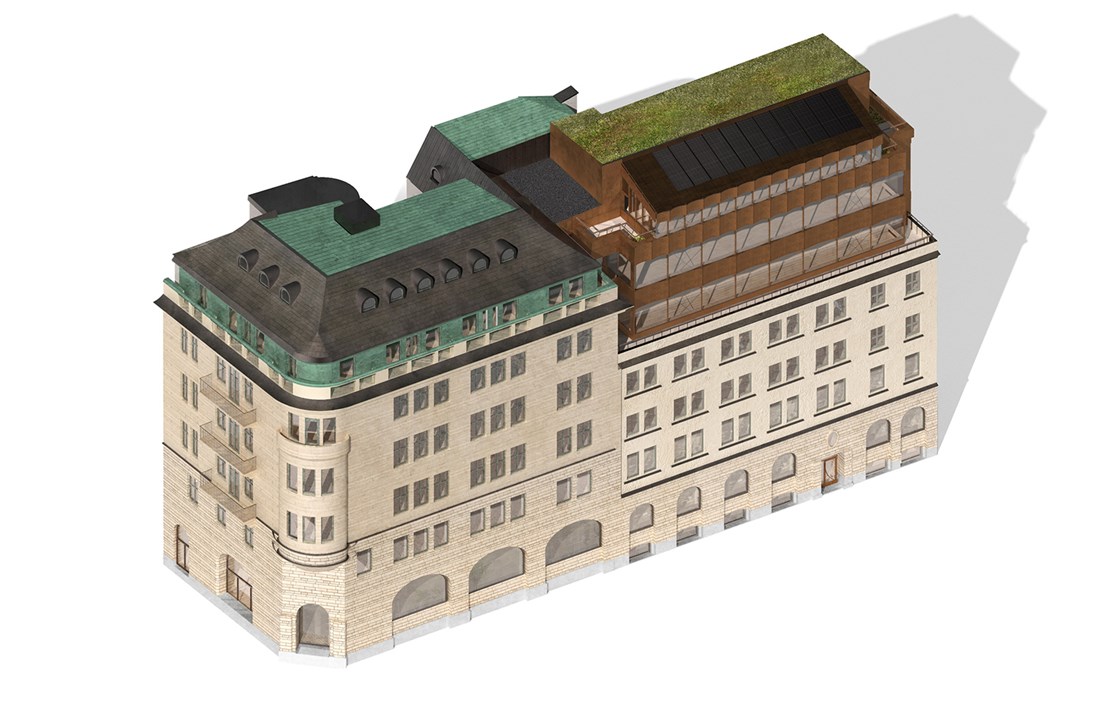

A prime example of how to pursue urban densification in a sustainable way and at the same time save both time and money is the Styrpinnen 15 property on the corner of Kungsträdgårdsgatan and Näckströmsgatan in the heart of Stockholm. The attractive fin-de-siècle edifice was designed by architect Erik Lallerstedt, and when it was built for Hernösands Enskilda Bank in 1889–1901, it marked the start of this district’s life as the city’s financial powerhouse.

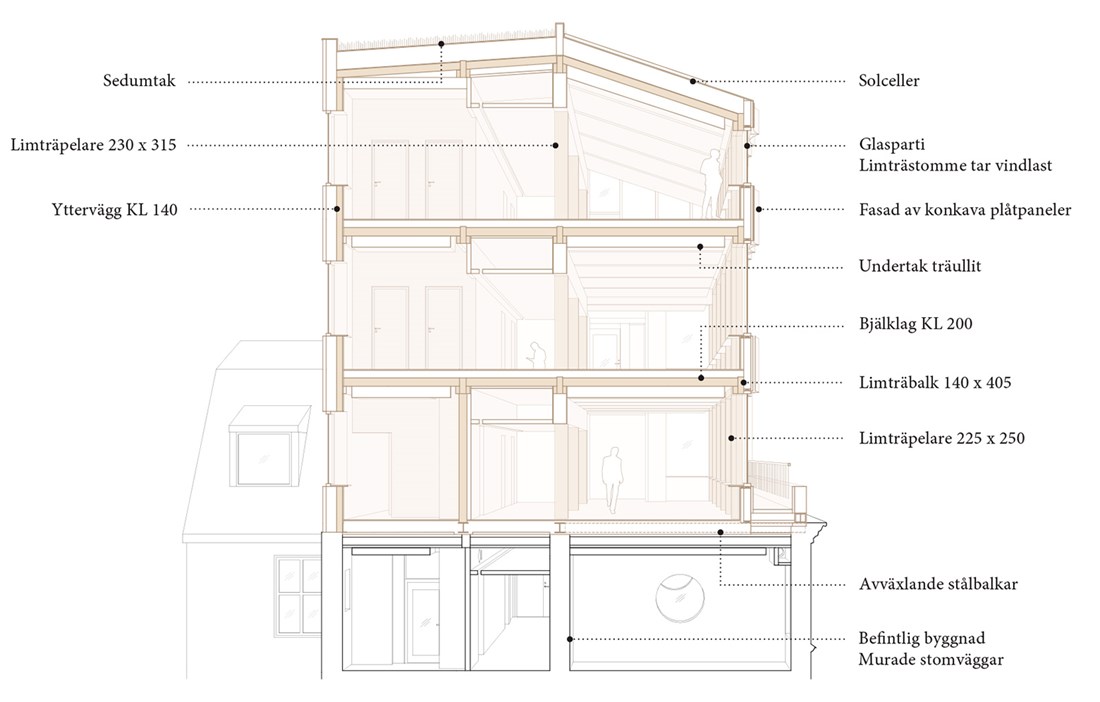

Since then, the building has been refurbished and redeveloped several times. Now Styrpinnen 15 is being fully overhauled by the current owner Vasakronan. In addition to having the foundations reinforced, the layout changed and new technical installations added, the building has also gained a three-storey upward extension using CLT and glulam from Martinsons.

“We began by focusing on the problem of the settlement of the old building. This meant that any addition would need to have as light a frame as possible. The choice of wood was therefore a necessary and pragmatic decision. Then there’s the fact that we as architects and Vasakronan as a property owner like the sustainability credentials of using wood,” says Morten Johansson, lead architect at Dinell Johansson.

Choosing CLT and glulam has brought numerous advantages. The structure’s lower inherent weight, coupled with the high degree of prefabrication, sped up the installation time, for example, which resolved many of the logistical challenges faced by a major construction project right in the middle of central Stockholm.

“Generally speaking, extending upwards in wood is a great means of densification within existing developments. From a sustainability perspective, it’s also better to create workplaces in areas that already have public transport and good local services. What’s more, our tenants seem to find the indoor environment in a wooden building more pleasant. In theory, this should make it easier for us to rent out premises and retain existing tenants in buildings with plenty of exposed wood,” states Vasakronan’s Sustainability Director Anna Denell.

With Styrpinnen 15, Dinell Johansson has approached the extension as a modern roof design that happens to be three storeys high, rather than as just adding three new floors. The extension stands out due to its wavy façade in sheet-metal, with its rust-brown lacquer that is reminiscent of newly oxidised copper. Internally, exposed beams and posts in glulam help to create a warm and welcoming atmosphere.

“When you’re doing an extension, it’s important to get to know and understand the old building. To read up on and be aware of its history and what has happened on the site. The modern wooden structure on Styrpinnen 15 become our way of flirting with that history,” says Morten Johansson.

New times mean new tenants. Once the revamped former banking centre is completed in autumn 2020, it will be a game developer, not a bank, that occupies the property’s 4,350 square metres.

In Solna, just north of Stockholm, Arenastaden has taken shape as one of Europe’s most modern urban districts. As the area has developed and grown, demand for hotel rooms has also increased. This has prompted Quality Hotel Friends to expand its business with the addition of over 250 new rooms, located in a CLT and glulam extension designed by Wingårdhs. The new hotel rooms are spread across three floors on top of the lower section of the existing hotel, which is called Arena Gate.

“When you look at modern buildings in concrete, they often have the capacity to carry a greater load than they were designed for. This opens up the possibility of adding an upward extension, and if you choose a light material like wood, you can go for more than one floor. That was why we chose a CLT and glulam frame when extending Arena Gate,” explains Gert Wingårdh, architect at Wingårdhs.

The extension has a black, fully glazed façade that follows the same pattern as the underlying building. The new façade is pleated to break down the scale, create a wave pattern and connect to the arena’s angular surface. To separate the extension visually from the original building, the lower floor is set back from the façade of the underlying structure. Although the hotel does not operate on the ground floor, the aim is for the extension to frame the site, light up and lend a welcoming feel.

“The drive for densification has helped, making upward extensions more common in attractive locations where more development is desired. And wood has clear commercial benefits in this respect. In addition to the material’s architectural possibilities, wood frames also have a significantly lower climate footprint. The fact is that wood is our first choice for the structural frame in all our projects these days,” says Gert Wingårdh.

And so we move north to the modern city of wood that is Skellefteå. Here there are many examples of words been turned into action when it comes to pushing forward with advancements in wood construction. A prime example is Skellefteå Kraft’s head office in the centre of Skellefteå. When the company needed more space to grow, they decided that the only way was up. The result was a CLT and glulam extension on top of the older of the two office blocks.

“The idea of doing an extension came up at quite an early stage. The main reason was that the head office is located in a densely developed area with no room for a newbuild. Going down the wood route was also the obvious choice, since Skellefteå has a wood building strategy that advocates sustainable building,” states Rolf Marklund, lead architect at Collage Arkitekter.

The structure, made entirely in wood, was supplied by local company Martinsons. Like the older parts of the head office, the façade is clad in copper.

“Both CLT panels and glulam allow for a high degree of prefabrication, which makes assembly more efficient and shortens the construction time. This was, of course, a major benefit considering that the existing building needed to be vacated for the duration,” says Rolf Marklund.

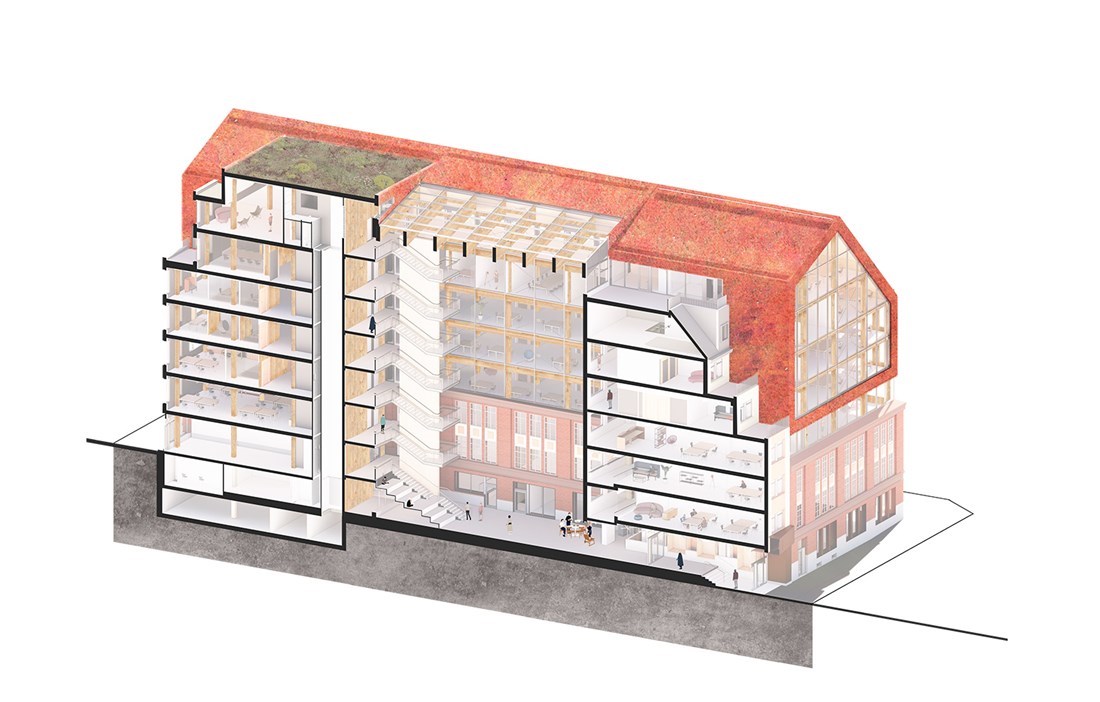

Back to the capital and the old industrial district of Hammarby Sjöstad, which in recent years has undergone a major transformation. Its crowning glory is the office building Trikåfabriken. Here, the original brick building from 1929 has been renovated internally and given a timber-framed extension rising up five floors. The project is a good example of how contemporary architecture can serve as a link between past and present.

“Using wood for the extension was quite an easy choice for us. In addition to the climate benefit, we knew that it would result in less reinforcement work and that savings could be made due to the faster process. We also saw huge benefits in exposing the wood internally, as it provides a healthier indoor environment and is a friendly material that is easy to live with,” says Matthew Eastwood, lead architect at Tengbom.

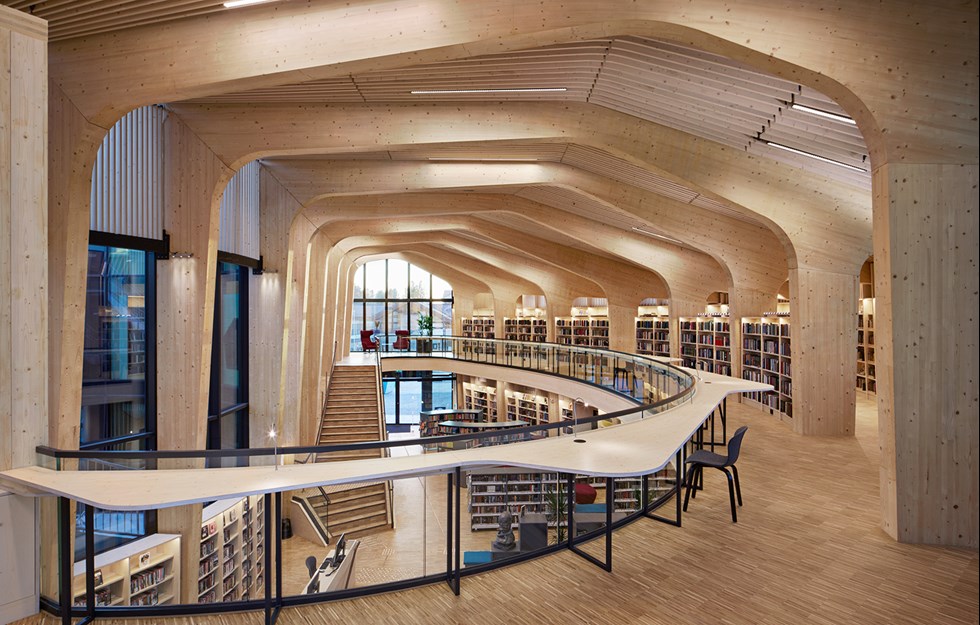

Wood is a prominent feature of Trikåfabriken and the load-bearing frame is part of the design. The material highlights an honest approach to design, where nothing is concealed. The ambition was to make it as clear as possible where old meets new, which is why the wood frame is exposed internally and visible from outside.

“Working with a wooden structure means that you have to think things through all the way to the end and see the material as an aesthetic asset within the architecture. An exposed wooden frame means that everyone involved has to be aware that this beam or this wall will be visible, from the people working on the planning and manufacture to those responsible for transport and assembly,” says Gustav Essebro, CEO of TK Botnia, which was responsible for the structural engineering work on the extension.

The four projects show that wooden extensions make it possible to increase density, extend lifetimes and use existing buildings in a more flexible way. Prefabricated wood building systems also enable us to build with a low climate footprint. This reduces the need for land and increases the scope to build in central, attractive areas where people want to live.

“It’s very much about cherishing what has already been built, both from a sustainability perspective and with regard to people’s living environments,” concludes Susanne Rudenstam.

Text Katarina Brandt